Siddharth Khajuria / Talks / Making Space: digital culture and the cultural sector

I was invited to give the keynote speech to open the Hello Culture conference in Birmingham, part of the BBC’s Digital Cities week in September 2018. I was asked to respond to the context for the day’s conference: NESTA’s recently published Experimental Culture report. In that report, NESTA wrote:

“Digital technologies, with their potential to lower the costs of production and enhance access to the arts and culture across a range of channels, have been championed as a means of democratising the supply and demand for arts and culture. In parallel fields, such as music, video games, television and film, digital disruption has led to wholesale changes in audience behaviours. However, arts and cultural organisations – in the main, still rooted in physical venues, artefacts or in-person performances – have been largely immune to these shocks.”

Here’s the text of the speech I delivered:

INTRODUCTION

I’m a Senior Producer at the Barbican Centre — a cross-arts organisation in London, with an arts and learning programme which ranges across theatre, music, visual art, and cinema.

What I want to do with my talk this morning is explore how digital culture can (and has) changed the approach institutions like the Barbican take to arts programming.

Before doing so, I’ll say a bit more about the corner of the Barbican I sit in.

I jointly manage a team called the Barbican Incubator.

We’re an evaluation, research and programming team which was established a couple of years ago to provoke and drive change in key areas of the organisation.

Two of us, myself and a producer called Razia Jordan, are responsible for a public programme of installations, events, and artist residencies — much of which is dedicated to exploring the impacts of digital culture on both how we live, and how art is made today.

And the other two members of the team, Laura Whitticase and Shoubhik Bandopadhyay, lead on the Barbican’s evaluation, research, and policy work.

Part of the reason the Incubator merges these functions in one team is to allow us to develop arts programmes which are directly informed by some of the insights from our research and evaluation work.

More broadly, the Incubator forms part of the Barbican Artistic Director’s (Louise Jeffreys) Division — so we sit alongside the Visual Arts, Cinema, Music, Theatre, Marketing, and Communications Teams. That “seat” at the same table forges a significantly more integrated and interrogative discourse about the organisation’s creative and strategic direction than might otherwise be the case.

WORKING IN INSTITUTIONS

Before getting into the main body of the talk, I ought to say a little bit about my perspective and where I’m coming from.For the entirety of my career I have worked at large-scale, publicly-funded cultural organisations. (I’ve been at the Barbican for six years now, prior to which I was a producer at the BBC).

I enjoy working in these places — they have huge power to shape our cultural tastes, sense of identity, and wellbeing. And many of them do so at scale.

But that means I need to emphasise that my perspective today is an institutional one — I spend a lot of time thinking about what makes them tick, and how to get things done in them.

When to be subversive, when to be upfront. When to ask permission, when not to. When to switch codes between the language of organisational strategy and the detail of a specific arts project.

Many people — especially those who work independently or for much smaller organisations — would likely come at the questions being asked by today’s conference in a very different way to me.

For me, the interesting challenge lies in thinking about how to engage with these institutions not as distant, abstract entities, but communities of people with a breadth of values and tastes and ideas that you can engage with and challenge.

I mention all of this by way of framing this as a talk that’s primarily concerned with how cultural institutions work, and — specifically — how a shift in mindsets catalysed by digital culture might encourage them to think differently about their art, their artists, and their audiences.

In particular, I’m interested in what this process — of using digital culture to interrogate institutional structure — might reveal about a series of important questions for the sector:

- how can we make publicly-funded culture more representative of the society which pays for it?

- how can our institutions become more responsive to an increasingly complex world beyond their walls?

- how can we make space for ways of thinking about and making culture which don’t find it easy to make it into our cultural organisations?

TERMINOLOGY

OK, Digital.I think most of us will have experience of digital being a much-abused term — deployed by managers, strategists, producers and artists in a plethora of ways.

So definitions are important, and I’m going to spend a couple of minutes talking about terminology.

One definition I’ve held onto, ever since it cropped up on his Twitter feed a couple of years back, was written by Tom Loosemore, one of the co-founders of the UK Government’s Digital Service.

He defines the challenge of digital as applying “the culture, practices, processes & technologies of the Internet-era to respond to people’s raised expectations”.

Now, my career has been spent grappling with this challenge within institutions which were conceived and created well before the internet was even the beginning of an idea.

So, the question I want to explore in this morning’s talk is a slight modification of Tom’s definition.

It’s this:

How do you apply the culture, practices, processes and technologies of the internet era to institutions that were created before it?

How do you square the pre-internet origins of most of our cultural organisations with the world we live in now?

The title of this talk — “making space” — hints at my answer to this question.

I think we can, by applying some of the cultures and practices of the digital age to our institutions, make new kinds of space — both physical and conceptual — for emergent forms of culture within our arts organisations.

When I say digital culture today, what do I mean?

Broadly speaking, I’m referring to the impacts of the internet and its technologies on the way humans communicate, collaborate, and create.

Specifically, I think it’s a mindset, or set of values which we’re seeing more and more in the business world, but less so in the arts.

It’s a set of values with which many of us in this room are probably quite familiar:

- agility

- responsiveness

- collaboration

- innovation

- experimentation

- customer-focus

Underpinning my argument today, then, are a couple of thoughts:

- That it’s these values, rather than any specific technology, which have the power to transform our arts organisations

- That they need to be applied to the whole organisation, and not an individual digital team or wing or art form.

STRUCTURE

OK — that’s a little bit on terminology, and the fact that my perspective is an institutional one.

I’ve structured the main section of my talk like this:

- Firstly, I want to reflect a little on the way in which I think most organisations respond to the challenge of digital.

- Then, I’d like to talk briefly about digital strategy. In particular, trying to create a healthier institutional dialogue around the topic.

- And thirdly, I’ll look at how some of these concepts have been applied in practice at the Barbican over the last couple of years.

OK – the first of those three sections.

1 – HOW DO WE RESPOND TO DIGITAL?

Just one last thing on terminology — when I’m talking about ‘content’ today, I’m taking it to mean the stories an organisation tells.And stories — in the context of arts organisations — means so many things: theatre productions, gallery exhibitions, online content, festivals, social media, workshops, public programmes. It’s everything which our participants and audiences see and/or hear from us online, or in real life .

Now there are, I think, two ways in which cultural organisations who are thinking about ‘content’ tend to respond to ‘digital’.

The first approach is to amplify our existing stories.

To carry on doing the kind of work we already do, telling the sorts of stories we already tell, but telling them to more people or telling them in more impactful ways.

And this is often brilliant:

- national and international cinema broadcasts have transformed the ability of audiences around the world to access live performance

- or the National Gallery uniting Van Gogh’s five sunflower paintings together for the first time, on Facebook.

- or increasingly innovative use of virtual and augmented reality technologies to draw audiences closer to the power of complex art forms.

This kind of activity does not seek to change our core programmes. And nor should it.

But when our focus is on amplifying existing stories, the people who are making and shaping the art — the artists, curators, and producers — largely remain the same.

And our energies are dedicated to amplifying their voices.

The second approach is to change our stories. Or at the very least, actively broaden the range of ones we tell.

Many of us are still figuring out what this might look like — but I thought it might be helpful to illustrate what I mean with a handful of examples…

- Rapid Response Collecting at the V&A — this is a programme — begun in 2014 — which allows the V&A to collect and display objects in response to major moments in recent history. They include the Oculus Rift headset, drones, election leaflets from the Brexit referendum, and much else. I think the key point here is that the V&A identified a need to be more responsive in their curation to what was happening in the world.

- Hack the Barbican — in Summer of 2013, we handed over control of our public foyer spaces to a self-organised collective of artists, technologists, and entrepreneurs. This community, who met every Tuesday evening at the Barbican over the course of the year to shape the project, grew to consist of nearly 300 people putting on a 100 or so public residencies and projects over the course of a month in 2013. There was no central curation and plenty of moments of imperfection in this project. But what struck me most was how the non-hierarchical and open-ended project posed serial challenges to an institution which doesn’t usually encounter these kinds of iterative and network-driven production processes.

- Scratch — This next example, Scratch, doesn’t have anything to do with digital technologies, but does have some principles rooted in digital culture. It’s a process by which Battersea Arts Centre in London encourages theatre makers to develop work — sharing ideas with audiences at an early stage in the process and iteratively refining them over and over.

- Immersive Storytelling Studio – and finally, the National Theatre’s Immersive Storytelling studio is worth touching on briefly, primarily because it’s a Theatre which has established an entirely new commissioning arm, focused on stories told with VR, 360, AR and other emergent tech.

I could, and probably should, spend much more longer delving into each of these examples — but for now I just want to note what I think they have in common. They’ve been conceived by institutions thinking about process, about the structures by which networks are formed or programming decisions are made.

What’s emerged from that thinking are approaches to programming which are more responsive, open, collaborative, and experimental than established cultural organisations tend to be.

Something to keep an eye on, additionally, will be how programmes take shape at entirely new organisations conceived and created for the digital age, and built to be significantly more flexible than previous generations of cultural centres.

In particular, I’m interested to see how the Factory in Manchester and The Shed in New York develop in the coming years.

They’re both explicitly designed to be much more fluid venues — resisting a structure defined by individual art form disciplines.

So, to recap, I think there are two approaches.

One – we amplify our existing stories.

Two – we change, or at the very least, add to them.

I should clarify that these two approaches are, of course, not mutually exclusive.

But… at least at a senior level — I think most organisations feel most comfortable with the first of these.

Because a commitment to amplifying and extending reach is premised on the idea that if only we could build a bridge between our existing programmes and new audiences, those audiences will embrace and engage with the work.

So we develop livestreams and event cinema and rich online content and much else.

And these initiatives have been vital to improving accessibility to the publicly-funded sector.

But the latter approach — geared more toward effecting structural change in pursuit of broadening the range of stories we tell — is what I want to focus on today.

Now, in some of our early conversations — Lara, who invited me to present this morning — mentioned this recent report published by NESTA, Experimental Culture.

That report touches directly on this question of structural change and I want to quote from it:

“…In parallel fields, such as music, video games, television and film, digital disruption has led to wholesale changes in audience behaviours. However, arts and cultural organisations – in the main, still rooted in physical venues… – have been largely immune to these shocks.”

I want to think about why this might be the case.

Firstly, if the majority of our efforts are invested in amplifying what we already do, rather than interrogating whether we’re doing all the right things in the first place, then we’re unlikely to see any transformation in our institutional structures.

Secondly, and this is in someways a more fundamental point, our strict definitions of culture in the UK are likely to preserve the status quo.

I’m going to turn to a passage from a book by the sociologist Mike Savage — it’s called Social Class in the 21st Century, and in it he outlines the concept of “cultural capital”.

He argues:

“…while there may be limitless types of cultural activity, ranging from gardening through to visiting the British Museum, watching Big Brother, or playing computer games, not all are valued equally. Some forms carry a cachet that is cultivated and reinforced by influential people and institutions…

What is sometimes called ‘high’ culture has been deeply promoted by the state. The vast majority of the Arts Council budget, for example, is spent subsidising ‘high’ art forms such as theatre, dance, and visual arts…”

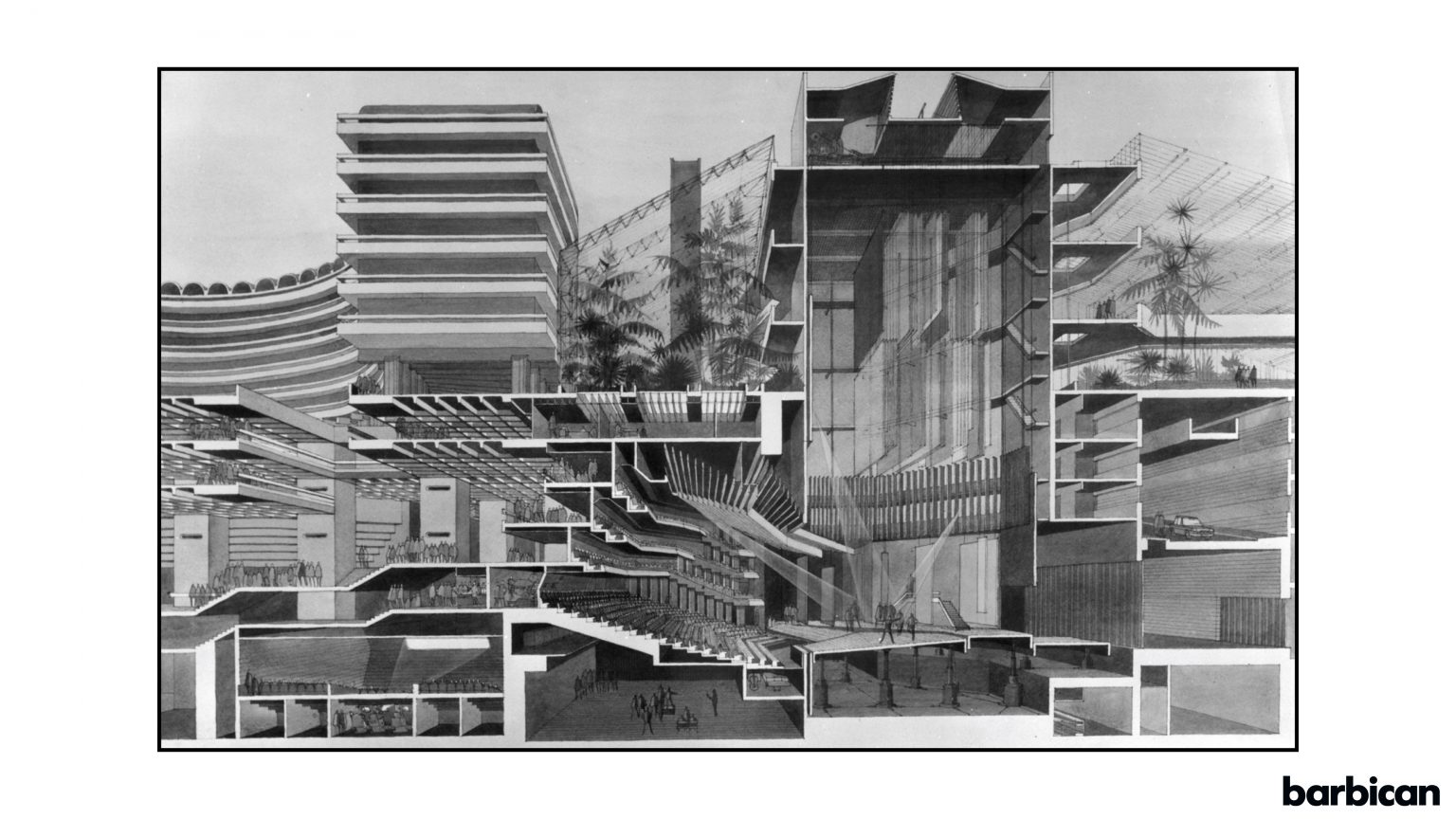

This is an observation which feels particularly relevant to the building I work in.

The Barbican’s architecture is designed to create (wonderful) homes for those forms of ‘high’ culture which have been promoted through public funding for decades.

But it is also true of the sector at large — the structure of the Arts Council budget has shaped the fabric of our cultural landscape.

However, the policy agenda feels like it’s just beginning to shift a little. I won’t go into too much depth on this, but just take a look at the questions asked by Darren Henley (Chief Executive) in his blog post introducing the issues the Arts Council’s next 10 year strategy is going to have to engage with.

Just a few examples:

- How is the world changing and how should our priorities reflect this?

- How can we become more open, accessible and diverse?

- How can we respond to the challenges and opportunities of new technology?

- Do we need more emphasis on participation?

Being able to answer the majority of these questions properly demands a meaningful engagement with more than just digital technology, it requires us to look at how we apply the impacts of digital cultures, tools, processes, and technologies to everything we do — beginning with what we programme in the first place.

But, if we’re keen to do this — to interrogate how digital might impact programming — then one of the first things we need to ensure is a healthy institutional (and sectoral) dialogue about digital strategy.

2 – DIGITAL STRATEGY

So, in this second section, I’m going to spend a few minutes talking about the Barbican’s digital strategy.I mentioned at the beginning that I used to be the Barbican’s digital producer, and still share responsibility with a handful of colleagues for our Digital Strategy.

I was one of those people — and I know quite a few of them — who have had “digital” in their job titles and found themselves drawn into conversations about an almost irreconcilable range of topics, from gallery apps, and online content, to fundraising, membership, and original programming.

And while I was sometimes grumpy about being stretched in this way, the cross-cutting nature of so many digital roles means that the people who hold them are often very well placed to learn how different teams think and what it is they want to achieve.

We can explore the grey areas in organisations, and conjure ways in which people from these different teams might come together in pursuit of a shared goal.

But the vagueness with which we used to deploy the word digital became increasingly unhelpful. Without any context to root it in, it is nowhere near a specific-enough term with which to have meaningful conversations. So, a couple of years ago, me and a few colleagues, wrote a short digital strategy for the Barbican.

I won’t talk through it all here, but I did want to outline it’s key premises:

- We don’t have a digital department – rather, we distribute specialists across existing departments, so you have an online content team within marketing, or a Head of Business Systems and Data, a Head of IT, a Head of Marketing, or myself — all of whose roles are more directly defined by digital culture than most.

- We don’t talk about ‘digital’ by itself – it only makes sense for us across a series of domains: communications, infrastructure, partnerships, arts and learning.

- We don’t talk about specific digital outcomes, or technologies – instead, we articulate a set of principles which inform our decision-making across the organisation’s different teams.

I’ve been thinking about this approach quite a bit in the last few weeks, preparing for this talk. I am wary of the way in which individual institutions or the wider sector sometimes separate conversations about ‘digital’ from those about programming, representation, audience development, or any other organisational imperative.

Marketers market, curators curate, producers produce, fundraisers fundraise — the value of digital lies in enabling them to do so in different ways.

There’s this passage from an old article in the Guardian – it’s from 2014, and was actually a piece about the advertising industry.

“The word digital means everything and nothing, focusing on it is the biggest distraction of a generation. When electricity became widespread at the turn of the 19th century it was just business in the electrical age, there weren’t electrical consultants or electrical agencies.

When new technology is really understood it fades into the background, all the proof needed that we’ve not really digested the power of digital.”

Now, the author Tom Goodwin wrote that four years ago, but every word of it probably still stands.

And the key thing for me here is this idea of fading into the background.

If we ban ourselves from using the word digital, if we don’t have digital departments, digital producers, digital strategies, then we have to start being specific about what it is we want to talk about.

Is it inclusion and equality? Accessibility? New audiences? New artists? Extending reach? Trying out a new piece of technology? Better wifi?

Today I’m talking mainly about content and programming — and programming into physical spaces, rather than online.

And I’m aware that, so far, I’ve spent most of my time talking quite a bit about concepts and theory. So, I’d like to — in this third section — spend some time focusing on what me and a few colleagues have been working on at the Barbican in the last two years.

3 – MAKING SPACE

At the end of 2015, my role shifted from being the organisation’s digital producer to a new role of Senior Producer, with responsibility for developing and managing a new programme of installations, events and residencies for our public spaces — something which is now called the ‘Level G Programme’.Part of the reason I was asked to take on this role is the fact that, as the digital producer, I had spent the previous couple of years getting under the skin of different parts of the organisation.

And putting a ‘digital’ person into this space felt appropriate given the fluidity and flexibility of the environment within which I would be building a programme.

For those of you who don’t know the building, the Barbican consists of multiple venues: a 2,000 seat concert hall, two theatres three cinemas, and two art galleries.

These venues house our primary art forms: music, theatre and dance, film, and visual art. And in between these core art form venue, lies this:

Our foyers.

For years, they’ve been something of an institutional no-mans land, as many of the shared central spaces of cultural institutions tend to be — they’re depended on by many of our teams, but not ‘owned’, or ‘programmed’ by anyone.

And over those years, our foyers gradually became home to a multitude of communities: freelancers, toddlers learning to walk, students revising for exams, concert-and-theatregoers who’ve arrived early for a performance, and many others.

It has become a rich and complex social environment. It’s also that increasingly rare thing – an open, civic space in the middle of London. But stripped of all of the chaos, noise, pollution, and traffic of the streets beyond.

I really enjoy developing work for this kind of site – and I think — and especially for institutions which were built before the internet, whose architectures reflect those art form silos — the foyers, lobbies, civic spaces of our cultural venues are increasingly important.

For a couple of reasons.

- firstly, and I think this point is particularly relevant to the subject of today’s conference. The interstitial nature of these public spaces feels like a natural home for digital arts projects which either blur the boundaries between art forms, or sit entirely beyond them. And this comes back to something I was talking about earlier — the need to create space for a more open and fluid platform alongside the venues which provide natural homes for those historically-prescribed art forms such as theatre, music, and visual art.

- and secondly, the fact that the space into which you’re programming is already home to a multitude of different communities, rather than being a blank canvas, forces you to think much more about the relevance and accessibility of your work. Audiences are usually stumbling upon your programme (rather than buying a ticket and crossing a threshold into an art gallery or theatre space) and that increases your responsibilities in terms of how accessible that work is.

So, anything we programme needs to take these two contexts into account.

But in addition to that level of site-specificity, we’ve developed three thematic criteria for this platform — and work we commission or produce needs to explore at least one of these:

- the impacts of digital culture on the way we live, and on the way in which art is made, shared, and consumed

- our cross-arts programming theme for a given year (so in 2018, this is The Art of Change – our season looking at the role artists have played in reflecting on, responding to, and provoking social and political change)

- the questions faced by the cultural sector as it grapples with a fast-changing world.

What do these projects look like in practice? I’ll talk briefly about three of them before delving more deeply into one which opened a couple of weeks ago.

- Firstly, Numina – this sculpture by Zarah Hussain — blending the art and design of Islamic architecture with her contemporary digital arts practice. I won’t say too much more about her piece, other than to mention it won a Lumen Prize for Digital Art, and is a commission which she’s credited with sparking a step-change in her career, and she’s won a major commission as part of next year’s London Borough of Culture programme in Waltham Forest.

(I should say that this commission was a relatively low-risk decision for the Barbican — as part of a new and experimental programme. But it’s one which has proved transformative for Zarah. Something it’s made me consider much more directly is the — often untapped — power cultural institutions have, and how conscious we are of when and how and for whom we use it).

- secondly, Real Quick – a new programme for rapid creative responses to the state of the world. These are mostly talks, but we anticipate performances and creative experiments as time goes on. There’s never more than four weeks between conceiving an idea and the event taking place — and the events are advertised to audiences with seven days notice.

- finally, something which took place a few weeks ago, Alternate Realities — a recent showcase of four interactive, augmented, and VR works from the Sheffield DocFest programme. We worked with the curatorial team at DocFest to take four projects from their Festival and present them in the Barbican, alongside a programme of related cinema screenings.

Developing a new programme in the context of an established arts organisation has been a gradual process — at the outset, we were essentially tackling a bureaucratic challenge: is it possible to make space for an events and installation programme in an area which doesn’t traditionally house one?

So, much of our first year or so of work was spent wrangling with a set of logistical and bureaucratic concerns?

- If our marketing team is currently organised by art forms and the learning department, how will they support these new projects?

- If there are multiple claims to a space from different Barbican teams — who arbitrates disputes?

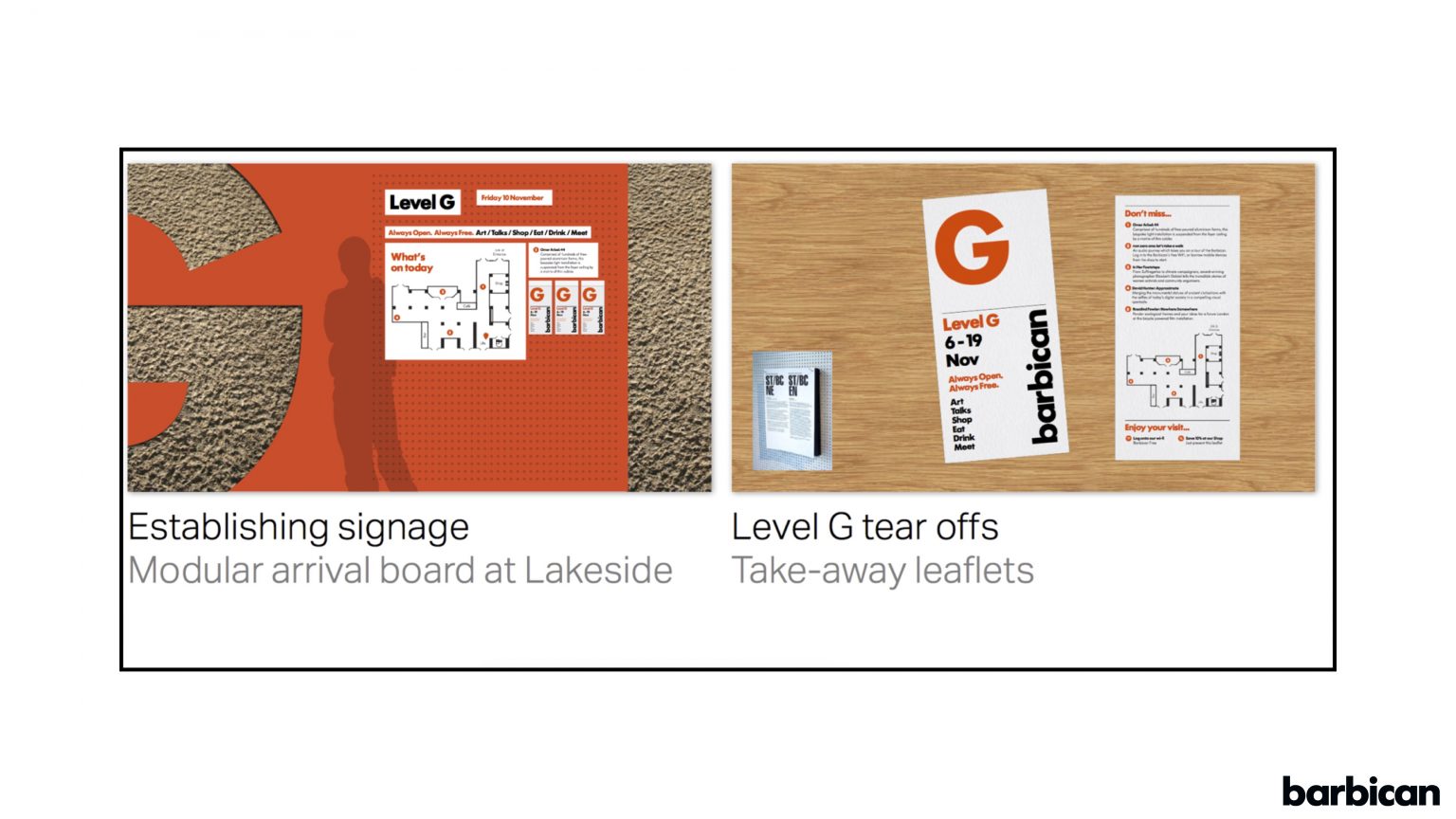

We’re not there yet, not by any stretch, but over time this programme of work has gradually developed a clearer sense of identity and purpose.

And it’s only this Summer, more than two years after it began, that we’ve arrived at a public identity for this programme, referring to it as the “Level G Programme”. We finally arrived at this form of words to describe the offer to audiences:

“Level G is our programme dedicated to transforming and reimagining our public spaces with site-specific installations, exhibitions and events. Creating spaces to visit, relax and discover the Barbican. Always open and always free.”

Now, what distinguishes this programme from the primary art forms at the Barbican is that it’s not defined by a discipline, or even an established venue. We don’t call it a “digital” or “visual art” or “new media” programme.

Rather, it is shaped by:

- those three thematic interests

- the social context of the space

- our approach to production

And with regards to this latter point, our emphasis in production for Level G is more and more is on co-curation and co-creation.

I’ll elaborate a little more on want I take those two terms to mean.

- by co-curation I mean that we’re working with partners who have expertise and networks beyond our own. A couple of recent examples include asking the Lumen Prize to co-curate an installation with us or the collaboration with Sheffield Doc/Fest.

- and by co-creation I mean that rather than commissioning an individual artist or auteur to author a piece of a work — we’ll often look to establish a process through which multiple participants gather around a shared interest point. It might be ageing, it might be young people’s mental health, it might be the impacts of machine learning. But they gather around that interest point to co-devise work. Hack the Barbican was perhaps one of our larger-scale attempts at this kind of work and there are some significant examples coming up in our 2019 programme, which we’re announcing later this week.

What both of these approaches have in common is a desire on our part as producers to actively distribute control beyond the curators and artists who traditionally wield it.

At this point, I want to talk in a little more depth about a project that we launched a couple of weeks ago: Soundhouse.

It’s a project which explores what a “cinema” for podcasting and creative audio might look like.

It looks like this — that structure is a collective listening cinema, a temporary new venue (for four weeks) where audiences venture into an experimental, womb-like space where they encounter 12-15 different pieces of audio documentary and storytelling.

I’ve been working with two independent curators — Nina Garthwaite of In the Dark Radio and Eleanor McDowall of Falling Tree Productions — to produce the project. Both of them have been immersed in the international world of audio and podcasting for years.

And the breadth and adventurousness of cultural expression in that space is breathtaking, but it is, largely, a “private” activity. Makers from all around the world craft stories, and listeners listen alone whilst driving, cooking, or lying in bed on the edge of dreams.

I’ll quote a little from Eleanor and Nina’s introduction to the project’s catalogue:

“Music, literature, art and film may all be enjoyed privately, and yet they all have a public life that connects them to the wider cultural landscape. Galleries, literary festivals and live concerts all create contexts in which our private enjoyment gives way to shared experiences…

The Soundhouse project has emerged from a question: What if radio and podcasting could occupy public space? What if those mediums could mark out territory in artistic institutions like the Barbican?… Would we think differently about the artistic ‘value’ of the medium, and how it’s funded, curated and critiqued? Would we do a better job of interrogating its structural problems?”

Of course, we commissioned Soundhouse because the increasingly important role of creative audio and podcasting in internet culture felt like important territory to address.

But I was also interested in how we might use the territory of a cultural institution to ask and address questions of what we value and what we call culture in the first place.

If we return to the question from the beginning:

How do you apply the culture and-so-forth of the internet era to institutions that were created before it?

then Soundhouse is one example of how we might answer it.

It entails constructing a venue-within-a-venue to make space for a set of cultural practices which wouldn’t otherwise have found and do not have a natural home in an arts centre.

Thinking about the impact of Soundhouse on the building, I’ve come to realise a couple of things:

- We can (if we want to) use our physical institutions to act as a conduit, of sorts, between culture which has an inherent publicness (like visual art and theatre and music) and that which is generally more private

- And, secondly, doing so in a venue like the Barbican with all of it’s cultural heft — invites a series of welcome conversations about cultural value, criticism, and audience.

In the weeks since Soundhouse opened, I’ve been reflecting on the differences between the way I produce and how, for example, a music programmer or gallery curator goes about their work.

I think the curators and programmers in those established art forms strive — in private, and often over the course of years — to develop the “perfect” expression of their, or an artist’s, ideas. There is a completeness to their work, and a focus on output above all else.

I think the work I do might be motivated by principles more readily found in the tech sector. I am happy, quite often, to make an experimental “minimum-viable” product public. And sharing a potentially unfinished idea or process with audiences, and reflecting on how they (and therefore the work) reacts.

This feels like the appropriate relationship between work and audience in public space, where there ought to be a feedback loop between multiple users of a shared civic environment.

But there’s also something about mindset here — app developers, product designers, website makers — never see the “first” release of a product as the final one, but rather the beginning of a process which, through it’s interaction with the real world, gradually improves the product being made — and gradually makes that product more relevant to the people its being made for.

Whereas arts organisations tend to produce complete or final exhibitions or productions and that’s what the audience sees.

I also mentioned Real Quick earlier, a programme my colleague Raz is managing.

It’s a platform which encourages artists and audiences to explore ideas and issues at moments when it feels urgent to do so.

It’s another programming strategy which feels like it has it’s roots in digital culture, rather than that of the established arts sector. It’s a little more experimental, more responsive and agile — and acts, deliberately, as a small counter-balance to the immaculate and years-in-the-planning work which audiences will find in our main venues.

It’s only in writing this talk that I’ve arrived at some of these insights — that my instinctive desire to work responsively, in a process-driven way, in dialogue with audiences and programming partners, as part of unlikely networks of people who share interests — that those are the same values that drew me to the intersection of digital and culture in the first place.

It stems from a belief that if you apply those values to established organisations, you can open them up and find a multitude of ways in which to make them more representative of the ways in which culture — broadly defined — is being produced today.

CONCLUSION

The longer we think of digital as a ‘separate’ thing, something which it’s the job of another team or person or expert or guru to solve, the harder it will be to answer this question.Our continuing deployment of the term, and tendency to create specialist “digital” roles does — to some extent — shield the core of an organisation from having to reckon with the digital present.

I was talking about the ideas in this keynote with a colleague who’s worked in this sector far longer than me. I’d been wondering about what occupied the space of “digital” in the sector’s discourse before it became an agenda.

She mentioned a few. And I think we know what they are, and they’re all still around.

Education, Creative Learning, Participation, Accessibility, Diversity, Inclusion, Internationalism, Regionalism, Partnerships, Sustainability.

Essentially, words you can put the word “agenda” after.

And the people who are charged with thinking about these agendas are often different people to the ones who are tasked with the core programming, curating, and producing roles.

And there is often a rich exchange between these policy and strategy roles on the one hand, and the implementation ones on the other. Where ideas and principles shaped by one corner of the organisation genuinely affect the way in which another looks at the world, and makes its decisions.

And I’ve seen it — the repeated presence of certain issues in our weekly conversations, the gradual implementation of new strategies, the arrival of new colleagues who are adept at navigating tricky conversations with old ones — have driven tangible changes in what our programme looks like.

And yet I wonder if what happens when you separate out any of these functions (Inclusion and Equality, Digital, Accessibility) — which aren’t things in their own right, but rather ways of thinking and working — is that you sustain an unhealthy split within a cultural organisation.

That split looks a bit, I think, like this:

- at the core, a set of art forms whose primary purpose is creating art which has intrinsic value. This is the “art for art’s sake” argument. Pure, and unconcerned (directly, at least) with wider socio-economic value.

- and then at the periphery, a set of teams (most often creative learning, public programme, public engagement) concerned with creating programmes of extrinsic value — programmes explicitly designed to create positive social good.

I really struggle with that division of labour. It can — and often is — reductively divided into a set of teams who care about “quality” in the middle, and around them, a set of teams who care about “doing good”.

As if to suggest the two are mutually exclusive.

I produced a talks event a couple of months ago which brought the English Cricket Board’s head of strategy, Vikram Banerjee, together with the Barbican’s Head of Music, Huw Humphreys — you’ll see why this is relevant in a minute.

They were there to share thoughts on their respective challenges in terms of widening engagement with cricket and classical music — two of our more established cultural pursuits.

Vikram has led a piece of work over the last years to launch something called the South Asian Action Plan — an impressive programme of measures to bridge the gap those who play cricket recreationally, and those who engage with the sport’s formal structures.

Vikram talked a little about the dialogue between his role (that of a strategist) and those concerned that his plans would reduce the quality of cricketers and coaches who would rise through the ranks. He recalled saying to a colleague:

“I control the process, you control the product”

That struck me as a really clear distillation of this issue — and it challenges this notion of intrinsic and extrinsic value as mutually exclusive. It made me think about how we might apply that thinking to the structure of a cultural organisation.

Let’s go back to that diagram which divides an organisation into two halves and re-imagine it — we can reframe a cultural organisation as a singular entity focused on world-class processes about, for example:

- digital

- inclusion and equality

- creative learning

- and so forth

which then shape the entire product of a cultural organisation.

I think I am someone who cares much more about the process than the output.

I have wondered whether, if you focus your energies on interrogating the processes themselves (curation, production, network-building, and so forth) — rather than the outputs, you’re much likelier to fashion a publicly-funded sector which feels relevant to a far greater proportion of the people who pay for it.

It’s telling, and probably quite important, that I haven’t mentioned digital much in this conclusion.

But these values which I’m talking about – a desire for a more open, engaged, representative, responsive arts sector are born from years of working at the intersection of digital and the arts, and feel like they are rooted in the values and philosophies of digital culture.

If we get it right, I think a meaningful engagement with digital culture can be a catalyst for major changes in our institutional programming.

Rather than simply amplifying what we do, it can be a new way of thinking about and interrogating the traditional silos within which arts programming takes place.

It should be a force which leads us to forge much-needed institutional space for a much wider group of artists, participants, collaborators, and audiences.

We shouldn’t restrict ourselves to thinking about online content, but open our institutional doors to all kinds of new spaces to reach and engage audiences, both physical spaces and virtual ones.

There is always space if you search for it… Thank you.